Black Designers Who Redefined Visual Culture: Part 1

Graphic designers whose work reshaped visual storytelling across publishing, advertising, and cultural history. From murals to logos, these creators left a legacy still shaping design today.

Once, the world of graphic design seemed narrow. People learned the names Saul Bass, Milton Glaser, and Paul Rand—not realizing that others had been quietly redrawing the landscape for decades. This series is about those figures: designers who turned their personal histories into visual language, even when the world wasn’t built for them to be seen.

Here’s the first half of that lineage—designers who blazed trails, shaped narratives, and brought creativity to new frontiers.

Charles Dawson (1898–1981)

Charles Dawson was far more than an illustrator; he was a cornerstone of Chicago’s Black artistic vanguard during the Harlem Renaissance‘s midwestern flowering. Best known for his elegant and influential advertisements, Dawson crafted a visual language for and about Black aspiration throughout the 1920s and 30s.

His journey began in 1898 in Georgia and led him to Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute. But his ambition soon outgrew its confines, propelling him to make history as the first African American admitted to the Art Students League of New York. He found its environment rife with prejudice, however, and soon departed for the more progressive halls of the Art Institute of Chicago, which he later described as “entirely free of bias.” There, he flourished, becoming a founding member of Chicago’s first Black artists’ collective, The Arts & Letters Society.

After serving in the segregated forces of WWI and facing combat in France, Dawson returned to a Chicago transformed by racial tensions and economic strain. Undeterred, he launched his freelance career in 1922, creating sophisticated artwork for a rising class of Black entrepreneurs. His pivotal role continued in 1927, when he helped orchestrate the groundbreaking first exhibition of African American art at his alma mater, “Negro In Art Week.”

His legacy was further cemented under Roosevelt’s New Deal. As a participant in the Works Progress Administration, Dawson lent his visionary talent to projects like the National Youth Administration, where he designed the powerful layout for the 1940 American Negro Exposition—a monumental series of dioramas tracing African American history.

Dawson’s prolific career came full circle when he returned to Tuskegee as a curator, a role he held until his passing. He is remembered not merely for his age, but for the profound depth of his contributions: a pioneering designer, a cultural architect, and an indispensable force in the advancement of African American art.

Aaron Douglas (1899–1979)

A major figure in the Harlem Renaissance. Aaron first made his mark with arresting murals and potent illustrations, crafting a visual lexicon that confronted the stark realities of race and segregation in America through a lens of elegant, African-centric imagery.

Beyond the studio, he was a catalyst for change. His co-founding of the Harlem Artists Guild was less a mere involvement and more a strategic opening of doors, creating a vital pathway for a new wave of Black artists to enter the public arena.

His final act was one of profound legacy: in 1944, he established the Art Department at Fisk University, shaping the program with his visionary pedagogy until his retirement in 1966. In doing so, he didn’t just conclude a career—he institutionalized his philosophy.

Widely revered as a foundational figure in modern African-American art, Aaron Douglas’s influence remains an enduring force, his work a permanent and inspirational fixture in the canon. His visuals look like rhythm incarnate—silhouetted dancers, geometric forms, and a fresh fusion of Art Deco and ancestral aesthetics. A central figure in 1920s-30s New York, his illustrations graced The Crisis and Opportunity, shaping the visual language of a generation. His mural cycle, Aspects of Negro Life, now lives at the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library—an enduring landmark in graphic storytelling.

LeRoy Winbush (1915–2007)

Winbush’s brushstroke traveled from South Side signs to national publications. He began designing flyers and murals for Chicago’s Regal Theatre and later served as the only designer of color at Goldblatt’s department store. He founded Winbush Designs, serving publications like Ebony and Jet. Known for his visual flair and community-centered work, he also taught design and even helped shape the coral reef at Epcot. His signature? Always being “a good designer first,” while steadily elevating overlooked stories.

Eugene Winslow (1919–2001)

Eugene Winslow was born November 17, 1919, in Dayton, Ohio, into a family where intellectual and creative pursuit was a given. The son of college graduates, he was one of seven children, all rigorously encouraged to excel in education and the arts—a foundation that would inform his life’s work.

His path first led him to Dillard University, where he earned a Bachelor of Arts in 1943. But with a nation at war, his service called; he enlisted in the famed 477th Bomber Group of the Air Force, cementing his place among the legendary Tuskegee Airmen. He attained the rank of Second Lieutenant and continued his service in the Air Force Reserve, honorably departing as a First Lieutenant in 1957.

Following the war, Winslow’s innate passion for art drew him to Chicago’s most prestigious institutions. From 1948 to 1951, he concurrently pursued post-graduate studies at the world-renowned Art Institute of Chicago and the groundbreaking Institute of Design at IIT. To support his craft, he masterfully navigated multiple disciplines—teaching, newspaper cartooning, advertising design, and engineering drafting—showcasing a versatile brilliance.

In 1963, a pivotal partnership emerged. Winslow co-founded Afro-Am Publishing, serving as treasurer and later vice president alongside Art Institute colleague David P. Ross. Their inaugural project was a masterstroke: Great Negroes Past and Present, illustrated by Winslow and published to coincide with the emancipation centennial. The book was an instant critical and commercial success, becoming the pioneering essential text for the nascent Black Studies movement. By 1972, it was in its third edition and officially adopted by the California Board of Education.

Ascending to president of Afro-Am in 1978, Winslow strategically pivoted the company’s model to a sophisticated mail-order operation, curating a catalog of hundreds of Black-interest educational materials targeted directly to educators, schools, and libraries. A visionary author in his own right, he penned *Afro-Americans ’76: Black Americans in the Founding of Our Nation*, further cementing his role as a key curator of African-American history. He presided over the company until its sale in 1993, leaving behind an indelible legacy upon his death in 2001. Winslow’s journey—from Tuskegee Airman to artistic pioneer to publishing entrepreneur—remains a profound narrative of service, intellect, and enduring cultural impact.

Georg Olden (1920–1975)

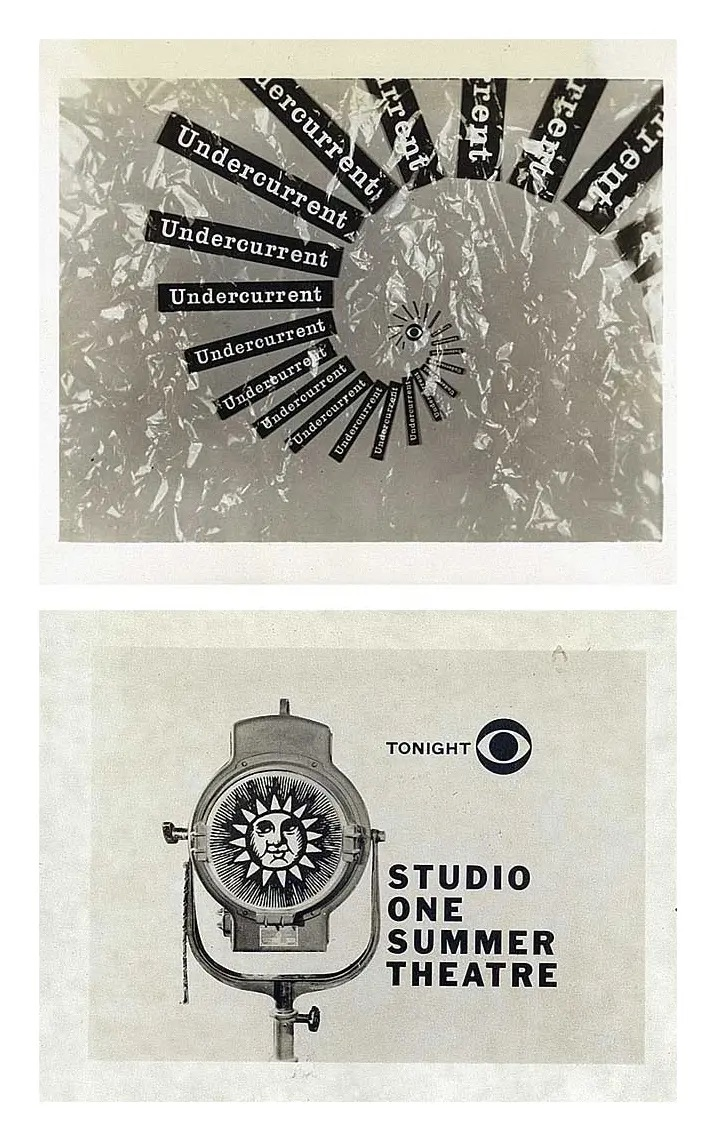

Born in Birmingham and educated in Virginia, Georg Olden, the grandson of a slave, didn’t just enter the world of television; he helped invent its visual language. Taking a position at CBS at the dawn of the broadcast era, he ascended to become the head of on-air promotions, effectively pioneering the entire field of broadcast graphics.

Working alongside the legendary art director William Golden, Olden was the creative force supervising the iconic on-air identities for a new American canon of television, including I Love Lucy, Lassie, and Gunsmoke. His influence extended beyond entertainment; he helped produce the vote-tallying scoreboard for the first televised presidential election in 1952 and collaborated with a roster of design luminaries like David Stone Martin and Alex Steinweiss.

His work was not merely seen—it was celebrated. Between 1951 and 1960, his name appeared over 100 times in prestigious industry annuals. By 1970, he had clinched seven Clio awards, having even designed the statuette itself—a sleek figure inspired by Brancusi’s Bird in Space.

But Olden’s legacy was twofold: he was a visionary designer who helped usher television into its golden age, and he was a potent symbol of Black achievement in a starkly segregated industry. He also made the first postage stamp celebrating the Emancipation Proclamation’s centennial and designed the televised 1952 election graphics. Ebony magazine profiled him repeatedly as a man who had seized the opportunities of a new medium, rising to an executive rank when, in 1954, fewer than 200 of television’s 72,400 employees were Black. His acceptance, as he noted with characteristic grace and pragmatism, was hard-won:

“In my work I’ve never felt like a Negro. Maybe I’ve been lucky.” It was a statement that spoke volumes, reflecting both his immense talent and the immense barriers he quietly transcended.

His awards from Clio and AIGA cemented his place as a creative visionary who shaped media visual language.

Thomas Miller (1920–2012)

Thomas H. E. Miller’s story is one of resilience and revolutionary talent. Honored as a pioneer at the DuSable Museum of African American History, he once addressed a captivated audience with the same clarity that defined his work. He recounted a familiar, yet deeply personal, post-WWII struggle: graduating top of his class on the GI Bill, only to be denied the promised job—an act of blatant racism. “But that didn’t stop me, obviously,” he stated, a simple phrase that belied the immense determination that followed.

That determination led him to Mort Goldsholl, where he would not just find a job, but forge a legendary 35-year tenure. At the non-hierarchical Goldsholl Associates, Miller was a creative force, helping to sculpt the visual identity of twentieth-century America. His genius is etched into some of the most iconic brands of the era: the sleek logic of Motorola, the optimistic spirit of the Peace Corps, and the crisp refreshment of 7Up.

A natural innovator and avid tinkerer, Miller’s curiosity knew no bounds. He moved fluidly between logo design, packaging, stop-motion animation, and exhibition displays, experimenting with techniques that would become foundational to modern video and digital graphics. His work fundamentally reshaped the aesthetic experience of a consumer society.

Yet, his legacy is dual: Thomas H. E. Miller was not only a master designer but a pivotal citizen who relentlessly challenged the racism entrenched within his profession. His career was a masterclass in using immense talent not just to create, but to overcome.